Table Of Content

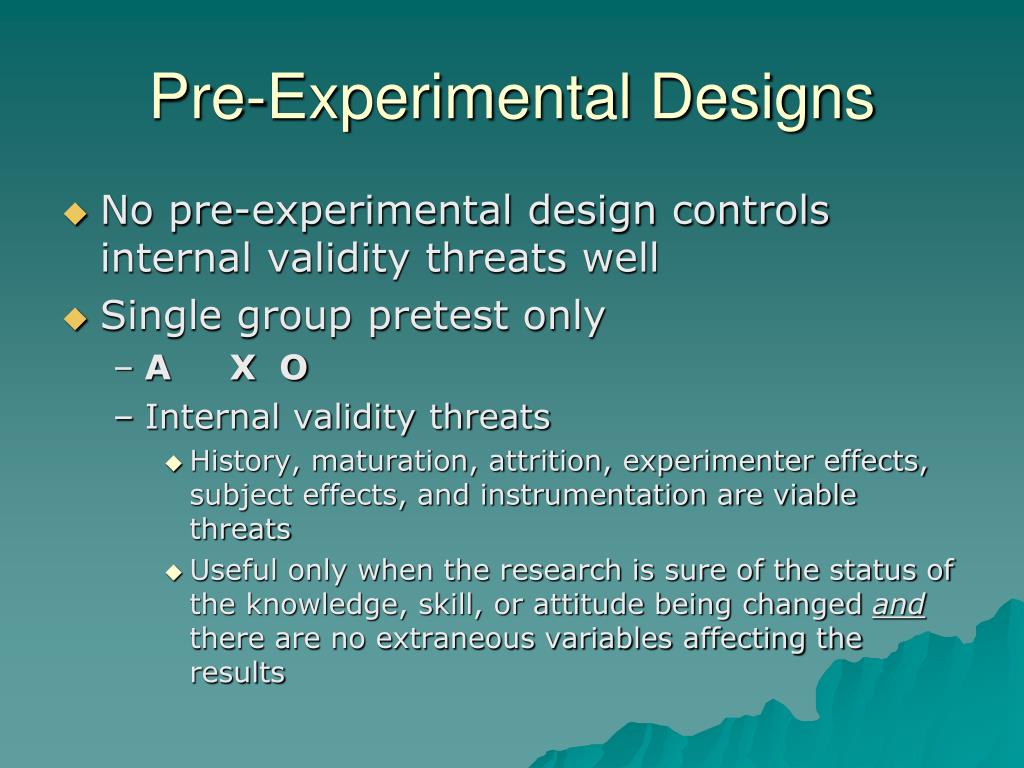

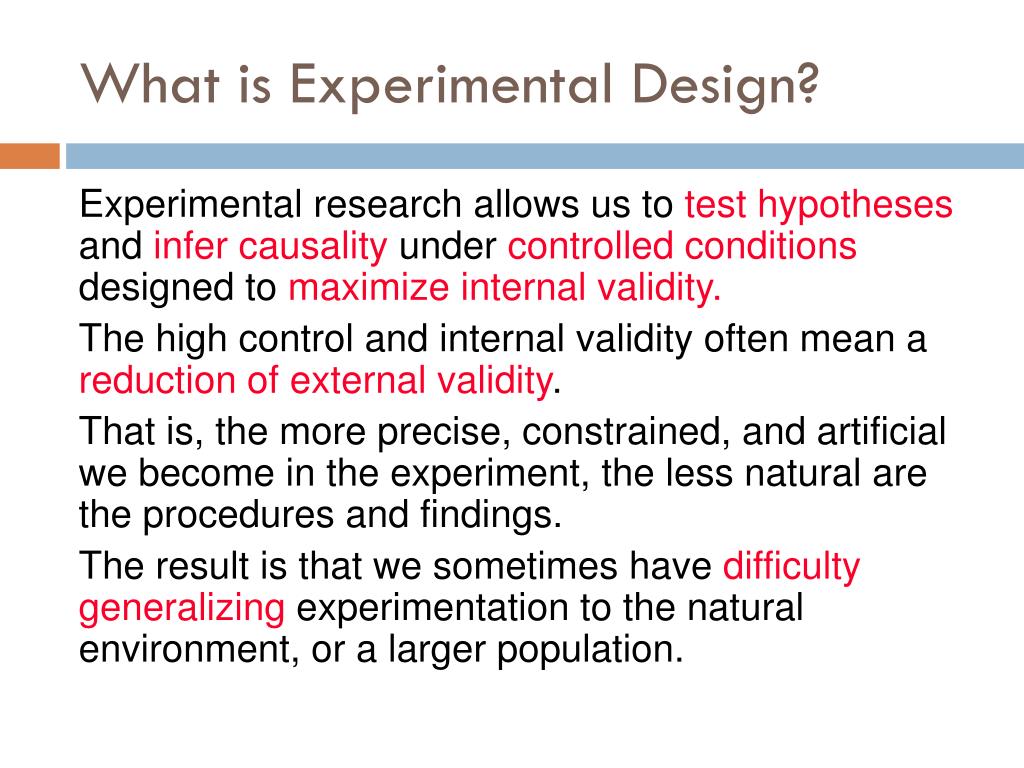

Assessments of research outputs should focus more on these factors and less on any apparent “novelty”. Even when pre-experimental designs identify a comparison group, it is still difficult to dismiss rival hypotheses for the observed change. This is because there is no formal way to determine whether the two groups would have been the same if it had not been for the treatment. If the treatment group and the comparison group differ after the treatment, this might be a reflection of differences in the initial recruitment to the groups or differential mortality in the experiment. The central challenge of the propensity score procedure is ensuring that the groups have been closely balanced on all important covariates. For example, matching on a few demographic variables is unlikely to represent fully all of the important baseline differences between the groups (Rubin, 2006).

2 Quasi-experimental and pre-experimental designs

Comparison of the teaching clinical biochemistry in face-to-face and the flex-flipped classroom to medical and dental ... - BMC Medical Education

Comparison of the teaching clinical biochemistry in face-to-face and the flex-flipped classroom to medical and dental ....

Posted: Tue, 13 Feb 2024 08:00:00 GMT [source]

If we wished to measure the impact of a natural disaster, such as Hurricane Katrina for example, we might conduct a pre-experiment by identifying a community that was hit by the hurricane and then measuring the levels of stress in the community. Researchers using this design must be extremely cautious about making claims regarding the effect of the treatment or stimulus. They have no idea what the levels of stress in the community were before the hurricane hit nor can they compare the stress levels to a community that was not affected by the hurricane.

Masters of healthy, sustainable, high-performance design.

Pooling refers to consultation with decision makers who have dealt with the problem of obesity in a similar population or setting. At this point, they should turn to the opinions of experts and experienced practitioners in their or similar settings (e.g., Banwell et al., 2005; D’Onofrio, 2001). Methods exist for pooling these opinions and analyzing them in various systematic and formal or unsystematic and informal ways. For example, Banwell and colleagues (2005) used an adapted Delphi technique (the Delphi Method, described in Chapter 6) to obtain views of obesity, dietary, and physical activity experts about social trends that have contributed to an obesogenic environment in Australia.

Scientific Inquiry in Social Work

Ludwig and Miller (2007) used this design to study some of the educational and health effects of the implementation of the original Head Start program in 1965. When the program was launched, counties were invited to submit applications for Head Start funding. In a special program, the 300 poorest counties in the United States (poverty rates exceeding a threshold of 59.2 percent) received technical assistance in writing the Head Start grant proposal. Because of the technical assistance intervention, a very high proportion (80 percent) of the poorest counties received funding, approximately twice the rate of slightly better-off counties (49.2 percent to 59.2 percent poverty rates) that did not receive this assistance.

Static-group comparison

In the static group comparison study, two groups are chosen, one of which receives the treatment and the other does not. A posttest score is then determined to measure the difference, after treatment, between the two groups. As you can see, this study does not include any pre-testing and therefore any difference between the two groups prior to the study are unknown. The authors of many of these guidelines state that their list might need adaption to the specific experiment. This is pointing out the general shortcoming that a fixed-item list can hardly foresee and account for any possible experimental situation and a blind ticking of boxes ticking of boxes is unlikely to improve experimental design.

There is also a risk of selection bias, and the findings may not be generalizable to other populations or settings. There are several types of pre-experimental designs, including the one-shot case study, the one-group pretest-posttest design, and the static-group comparison. As a result, it’s difficult to determine whether observed changes are the result of the intervention or due to extraneous factors. Pre-experimental designs are characterized by their simplicity and ease of execution.

EAn In-Depth Look at Study Designs and Methodologies

These designs are called “pre-experimental” because they precede true experimental design in terms of complexity and rigor. The true experimental design carries out the pre-test and post-test on both the treatment group as well as a control group. It does not always have the presence of those two and helps the researcher determine how the real experiment is going to happen. As pre-experimental design generally does not have any comparison groups to compete for the results with, that makes it pretty obvious for the researchers to go through the trouble of believing its results. Because there is a chance that the result occurred due to some uncalled changes in the treatment, maturation of the group, or is it just sheer chance. This design attempts to make up for the lack of a control group but falls short in relation to showing if a change has occurred.

Therefore, researchers must exercise extreme caution in interpreting and generalizing the results from pre-experimental studies. Much of the published evidence in obesity-related research is epidemiological or observational, linking the intermediate causes or risk factors with obesity-related health outcomes. Therefore, the range of values of moderating variables (demographic, socio economic, and other social factors that modify the observed relationships) in models that predict outcomes is limited. Because of these limitations of the evidence-based practice literature, decision makers must turn to practice-based evidence and ways of pooling evidence from various extant or emerging programs and practices.

Static-Group Comparison

It begins with researchers thinking about what variables are important in their study, particularly demographic variables or attributes that might impact their dependent variable. Then, the matched pair is split—with one participant going to the experimental group and the other to the comparison group. An ex post facto control group, in contrast, is when a researcher matches individuals after the intervention is administered to some participants. Finally, researchers may engage in aggregate matching, in which the comparison group is determined to be similar on important variables. Social welfare policy researchers often look for what are termed natural experiments, or situations in which comparable groups are created by differences that already occur in the real world. Natural experiments are a feature of the social world that allows researchers to use the logic of experimental design to investigate the connection between variables.

An example of an ecological model that illustrates the matching process is the Multilevel Approach to Community Health (MATCH) model of B. The MATCH model suggests the alignment of evidence with each of the four levels shown by the vertical arrangement of boxes in the figure. Finally, if a researcher is unlikely to be able to identify a sample large enough to split into multiple groups, or if he or she simply doesn’t have access to a control group, the researcher might use a one-group pre-/posttest design. In this instance, pre- and posttests are both taken but, as stated, there is no control group to which to compare the experimental group. We might be able to study of the impact of Hurricane Katrina using this design if we’d been collecting data on the impacted communities prior to the hurricane. Without having collected data from impacted communities prior to the hurricane, we would be unable to employ a one-group pre-/posttest design to study Hurricane Katrina’s impact.

Differences in breadth will be reflected in choices of the population(s) covered (e.g., defined by age, gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status), the range of diseases considered, and the types of costs to include. These decisions will be driven by the perspective taken in the study, as well as by available data. In a static-group comparison, there are two groups that are not created through random assignment. One group receives the treatment and the other does not, and the outcomes are compared.

As you might have guessed from our example, static group comparisons are useful in cases where a researcher cannot control or predict whether, when, or how the stimulus is administered, as in the case of natural disasters. Unfortunately, it is difficult to know those groups are truly comparable because the experimental and control groups were determined by factors other than random assignment. Quasi-experimental designs are similar to true experiments, but they lack random assignment to experimental and control groups. The most basic of these quasi-experimental designs is the nonequivalent comparison groups design (Rubin & Babbie, 2017). [1] The nonequivalent comparison group design resembles the classic experimental design, but it does not use random assignment.

No comments:

Post a Comment